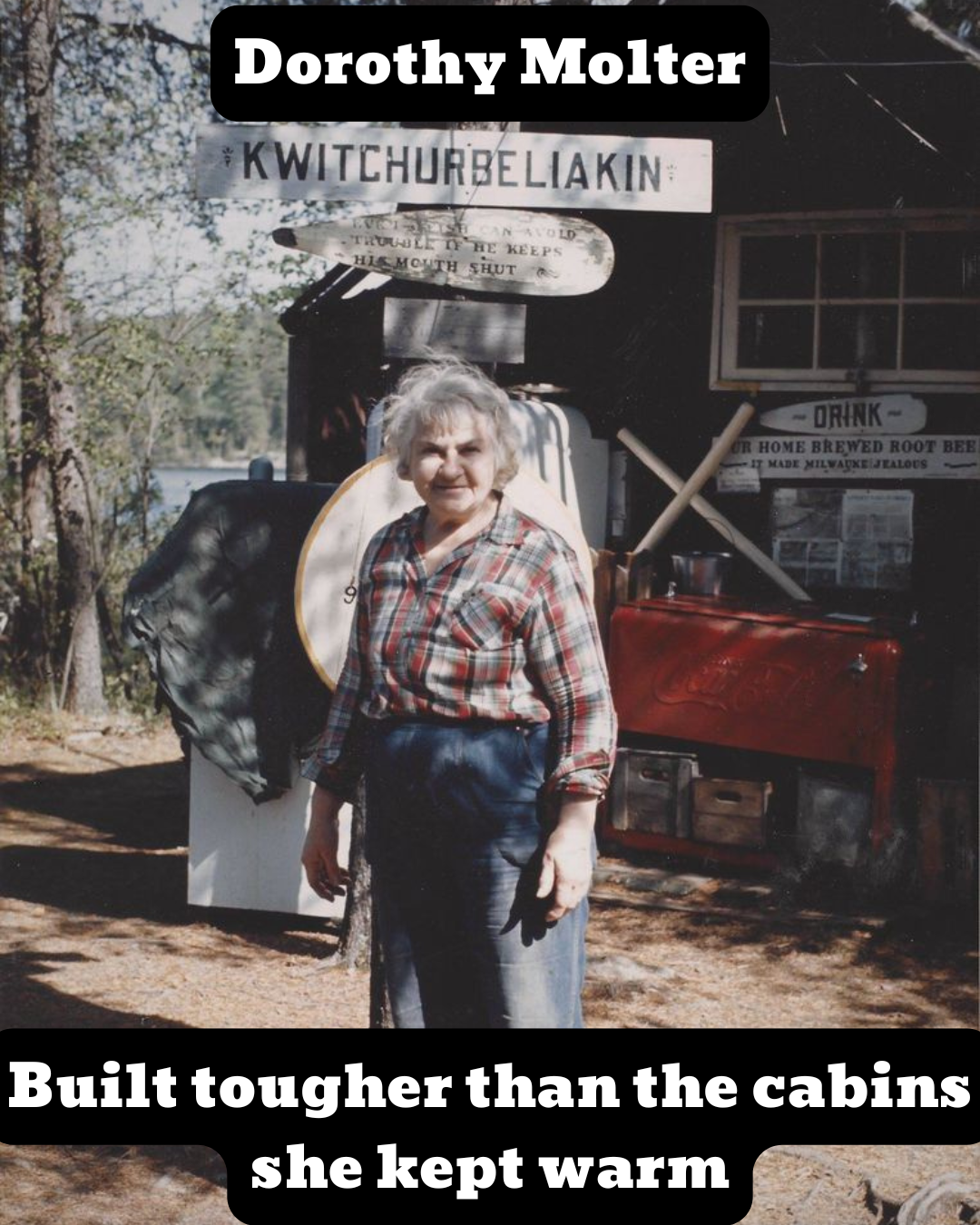

Dorothy Molter: The Woman Who Wouldn’t Leave

Share

They called her the Root Beer Lady.

But she was a hell of a lot more than that.

Dorothy Molter lived deep in the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota, once the site of a rustic wilderness resort — fifteen miles from the nearest road, five portages in, and about as far off the grid as a person could be without falling off the map entirely. And she didn’t just visit the wild. She stayed.

She first arrived at the Isle of Pines Resort in the early 1930s as a nursing student on a canoe trip and returned year after year to help out. After the death of the resort's owner, she took over operations and eventually made it her permanent home. She lived alone in that remote cabin through brutal winters and buggy summers for over 50 years. No electricity. No plumbing. No backup plan. She hauled water from the lake. Chopped wood to stay warm. Brewed her own root beer in reused bottles. And every year, she welcomed thousands of paddlers who stopped in not just for the drink — but to feel a little of what she had: peace, resolve, and the kind of solitude that only comes with choosing it.

Winter Wasn’t a Season. It Was a Way of Life.

While most people were fumbling through their thermostat settings or complaining about ice on the windshield, Dorothy was hauling sleds of supplies across frozen lakes and snowshoeing to check her traps — mostly for snowshoe hare and the occasional marten. She wasn’t running a fur operation; she trapped primarily for meat during the lean months, though she'd occasionally tan the hides for insulation or trade. She wasn’t playing survivalist cosplay. She was just living. Day after day, year after year.

She was a trained nurse, too — often the only medical help for miles. One paddler recalled gashing his leg badly on a rock and making the trek to Dorothy's cabin, where she cleaned, stitched, and bandaged it with calm precision — then handed him a warm meal and a root beer like it was just another Tuesday. Another time, she treated a man for severe burns after a camp stove explosion, keeping him stable until he could be evacuated days later. She’d patch them up without asking questions, feed them, and send them on their way with a smile and a bottle of homemade soda.

And When They Told Her to Leave — She Didn’t.

In 1964, the government passed the Wilderness Act, and the area she lived in became officially off-limits to permanent residents. They told Dorothy she had to go. She told them no.

Letters poured in. Thousands of them. From hunters, anglers, hippies, gearheads, old-timers, and kids who remembered that cold bottle of root beer after a long paddle. She didn’t ask for a fight — but people brought it for her anyway.

And they won. After nearly a decade of public pressure, letters, and advocacy, Congress made a one-time exception. She became the last legal resident of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. The only person allowed to stay in a place the government said no one could live.

She wasn’t loud. She wasn’t political. She just refused to leave what she loved.

A True Misfit

Dorothy Molter didn’t blend in. She didn’t try to.

She didn’t chase comfort, status, or convenience.

She chose hard paths, cold winters, and a life that made sense to no one but her.

That’s what makes her a misfit — not because she didn’t belong, but because she refused to change to fit a world that had lost its bearings.

She didn’t need the world to get her.

She just needed a lake, a fire, and the quiet howl of winter wind.

And maybe a bottle of root beer.